December 2018

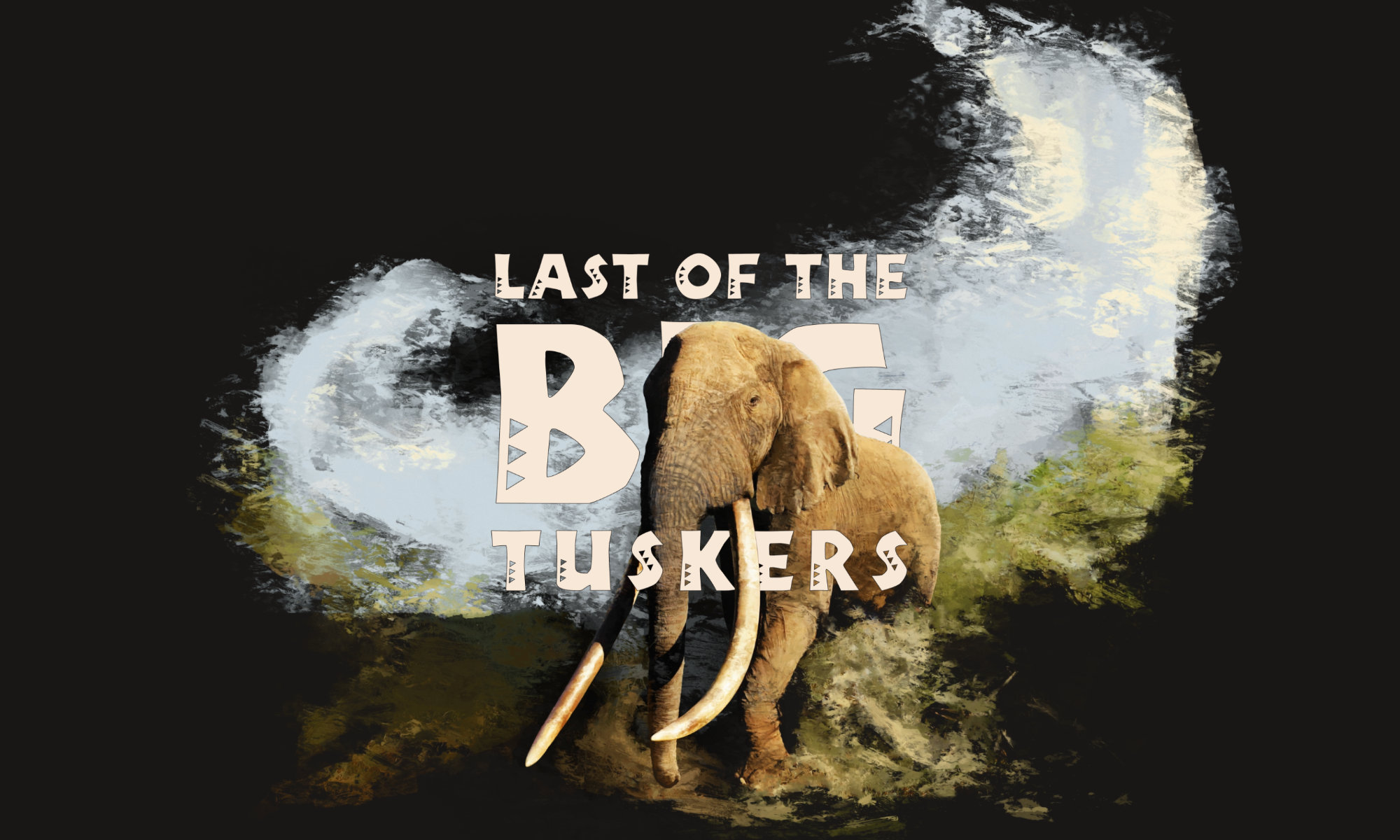

Last of the Big Tuskers

Dane Aleksander, art director at Animat Habitat.

This article is continued from Wildlife Documentary – Action. This ‘action’ set features a last documentary: Last of the Big Tuskers—a film by James Currie. The film entered festivals in 2018.

Last of the Big Tuskers cover art © Umboko Productions [bigtuskers.com]

Last of the Big Tuskers (2018)

59min

Last of the Big Tuskers is an Umboko Productions documentary film about the role of dominant elephant bulls in elephant social structures. For a documentary that looks at the lives of elephants, the film focuses uniquely less on the matriarchal herds, telling a story of elephant conservation instead in the context of the other elephant groups: askari bachelor herds.

These elephant bulls, called askaris, follow in the footsteps of a patriarch—a biggest bull elephant, likely with the biggest tusks, in the area. The increasingly few elephants with tusks estimated in excess of one-hundred pounds per tusk are known as super-tuskers. This film explains that the tusks of bull elephants grow at an accelerated rate when the bull is coming of age. When an elephant with the genetic makeup for big tusks has just reached the physical maturity of a super-tusker, that elephant becomes a prime target for poaching at the same time as that same elephant has just reached prime age for breeding. In the populations that remain of elephants in the wild, the result is that the genetic makeup for big tusks is artificially devolved.

The ivory trade remains a reality that is impossible to ignore when addressing a future for elephants.

Tusks are more than an indication of social stature for elephants. Elephants need their tusks to survive: to forage, to dig for roots, to dig for water, to strip bark from trees, to topple trees, to defend themselves. Elephant bulls use their tusks in combat for access to females in estrus. The film emphasizes the role of older bull elephants, who have become the father figures that young askaris have not had in the matriarchal herd. Old bulls show the ways to water and to survive the challenging landscapes, as well as teach discipline to the young bachelors.

Far too often, and for too long, elephants have been poached for their ivory tusks. For the few years leading up to this film, on average, almost one hundred elephants have been killed every day. Every dead elephant is a tragedy for a family-based herd and increasingly for the survival of the highly-intelligent species. The hope for this project is to share the value in keeping elephants alive, in particular big tuskers.

Every now and then… Everyday, people become evermore desensitized to the ways in which we take advantage of nature, wild or otherwise. This is known as a baseline shift—a baseline that represents what we think of as normal, which changes with every generation. Enter: director and on-camera co-host of Last of the Big Tuskers, James Currie, who grew up in South Africa, and who returns in this film to see the last big tuskers in Tembe Elephant Park.

Tembe Elephant Park, South Africa, has a unique topography: sandforest. This special sandforest shares a border with Mozambique and holds an elephant population with very special characteristics, as Alois Haberhauer, Elephant Geneticist at the University of Kriel, described in the film: “a special genetic makeup to produce strong tuskers.” Leonard Muller, Elephant Monitor at Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, also in the film explained the special circumstances for the elephants in Tembe:

“From a genetics standpoint [the elephants in Tembe] are quite gifted. Actually, it has a lot to do with the history of the area as well—that this must have been a very difficult area to hunt in the peak of the ivory trade so that would have left a lot of these bulls alone—that they were not hunted back then for their ivory. Tembe has got a lot more tuskers than anywhere in South Africa per population size. Even if you compare to a place like Tsavo, which is a massive park with lots of elephants, they only have a handful of tuskers [per population size]. So that is something quite special for Tembe.”

James Currie and co-host Tom Mahamba, then a senior ranger at Tembe Elephant Park, travel to Kruger National Park in South Africa and then on to Kenya to compare the elephants of other national parks: Amboseli, Chyulu Hills, Tsavo, to the last big tuskers of Tembe. The direction of the film remains centred on challenges facing elephant conservation today, pointing to tourism as a solution: managing the revenue from tourism to support the national parks as well as the communities who continue to co-exist on the front lines of a conflict with elephants. The same elephants that people all over the world – everyone, everywhere – so clearly uphold in story and in art.

“There is mystery behind that masked grey visage and ancient life force, delicate and mighty, awesome and enchanted, commanding the silence ordinarily reserved for mountain peaks, great fires, and the sea. ”

— Peter Matthiessen, The Tree Where Man Was Born (1972)

Last of the Big Tuskers title lettering © Umboko Productions [bigtuskers.com]

The film crowdfunded US$25,000 in a campaign in 2016, and entered festivals in 2018 in the United States as well as in South Africa.

The art of Last of the Big Tuskers (2018) was created probono by Dane Aleksander.

The film is dedicated to the memory of Tom Mahamba.

Last of the Big Tuskers (2018) is not yet rated.

Last of the Big Tuskers – Official Trailer (2018).

Last of the Big Tuskers (2018) is available on Vimeo on Demand.